Changing the narrative: celebrating South Africa’s young scientists

Whether they’re making their own stone tools, squeezing through caves or making anthropology accessible to more South Africans, our country has a vibrant cohort of young scientists who are doing their bit to uncover humanity’s origin story. During Youth Month this year, we decided to turn the spotlight on them.

We asked a selection of these bright young people how their love for science began, what it’s like being a scientist in South Africa in 2020, and to tell us some of the best and worst things about their chosen fields.

“It’s about making science accessible.” – Jesse Fredericks, biological anthropologist

“I’ve always thought the skull is pretty cool. I’ve never been a fan of ‘parrot’ learning, so I really enjoyed biological anthropology in my final year as an undergraduate, because we were taught in a way that encouraged us to think and to ask questions, and to search for answers. For me, it’s really about making science accessible and doing work that means something to the communities and people affected by it, and not just doing science for the sake of science.

“I find we tend to be more open about what we find problematic within our fields, and that we tend to seek out slightly older scientists who are able to bridge the gap between ourselves and some of the older academics and scientists. I think this gives us an opportunity to make science more inclusive and to add to the field with innovative ways of approaching problems.”

“The world and academia are going through a lot of changes.” – Kimberley Chapelle, palaeontologist

“I have loved science and anatomy from a young age, probably thanks to my dad, who used to tell me all of his stories from when he worked as a paramedic and GP. I really wanted to be a vet, but in the course of my undergraduate studies realised it wasn’t for me. I took a palaeo course in third year and realised that it merged two fields I really enjoyed: anatomy and evolution.

“There have been many stories worth telling. My first international collections visit was to Germany. I was terrified of breaking a fossil. At the time I thought it would mean instant expulsion from the collections – it turns out fossils break; the key is to report it so they can be fixed. I managed to not break anything. My supervisor, on the other hand, broke the fossil bone I was showing him within about 10 minutes!

“The world and academia are going through a lot of changes at the moment. I am glad I am part of this generation of scientists and that I get to witness and hopefully participate in bettering myself as a researcher and making palaeontology more accessible in South Africa.”

“Young people need to ask themselves the role they would like play.” – Beverly Makopo, lecturer

“I’m currently in the tourism field and my research focus is cultural heritage tourism. All young people who are interested in this field need to read more about it before starting their career paths. I’m an advocate for education; thus, obtaining a degree in the field is essential, because it will lay a solid foundation. Young people need to ask themselves the role they would like play in the industry.

“Moreover, the technological shift has made it possible for anyone to be visible and reach anyone globally; therefore, I encourage them to use such technology – for example, social media – to create their profiles and grow their network communities, especially with people in the field they are interested in. I know it may not be easy, but it is not impossible.”

Beverly began her journey into this field as a guide at Maropeng.

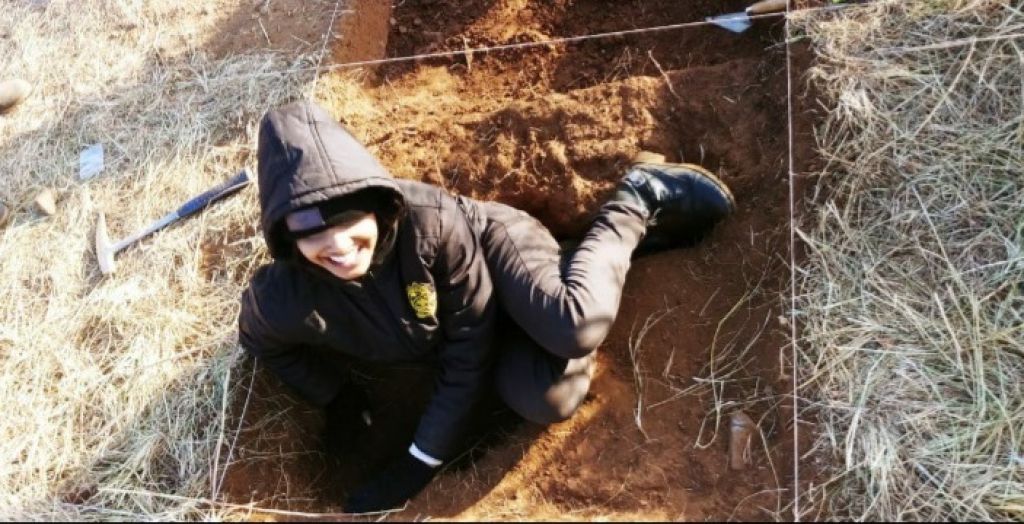

“The Maths part is actually very fun for me.” – Nicci Sherwood, archaeologist

“I have always loved science, and archaeology touches on multiple fields of the sciences. I get to do knapping [the art of making stone tools] for my research and analyse data with various statistics; the Maths part is actually very fun for me. Do research about archaeology to find out what interests you most, as the field is quite large. Ask archaeologists about anything you find interesting or have questions about. We will always try to help. This year is pretty bad for us all … although more awareness of minorities is being seen, which is huge plus.

“There is still a lack of awareness about autism (Asperger syndrome) in the field, which does make life for those of us with it challenging from time to time.”

“The best part about my job is being inquisitive!” – Daniel Tasker, archaeologist

“I have enjoyed discovery ever since I was very young. However, a chance finding led me into the wonderful world of the Acheulean in the Cradle. Holding the same implement that was held by someone a million years ago is a truly breathtaking experience. A link to the past, existing, yet absent at the same time.

“The best part about my job is being inquisitive! I’m constantly challenging my own ideas and opening a murky portal into a past that no one knows. I couldn’t describe a better job. It means a great deal, putting not only South Africa, but Africa as a whole, at the front of the scientific community.

“New ideas and fresh perspectives into long-researched beliefs are a must. South Africa is full of opportunity as there is a large wealth of archaeology that remains undiscovered and I feel lucky to be where I am today.”

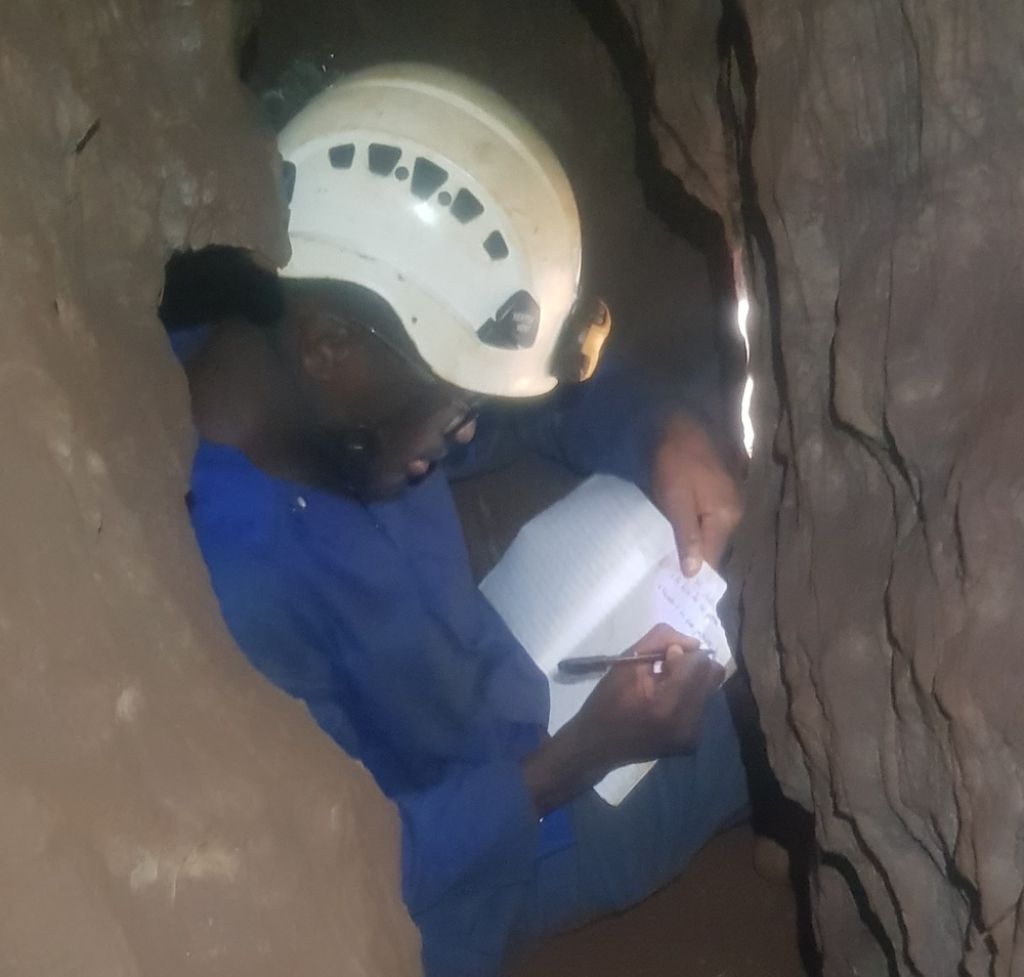

“It is an incredible opportunity.” – Tebogo Makhubela, geologist

“The discovery of Australopithecus sediba at Malapa cave was my very first attraction to the field of research around human evolution. I remember watching the announcement on TV. Prior to that I had visited the Sterkfontein Caves and Maropeng Visitor Centre on two school trips, and had already been interested in the story of human evolution. But it was not until I got the opportunity to do my MSc with the Malapa site as the study locality that I decided to channel my research towards the field.

“The best thing about my research job in the Cradle is the ability to work with a diverse grouping of people in terms of the countries they come from and, more importantly, the different fields of science they operate in. The exposure is unparalleled. It means a lot. It is an incredible opportunity, especially for first-generation university graduates like myself.”

“We get to communicate about the importance of anthropology.” – Mpume Hlophe, biological anthropologist

“When I was in high school, I helped out at the school museum and archives. After matric, I worked there as an intern while doing my Bachelor of Arts in Information Science. During my time at the museum and archive I would read about Dr Lee Berger and his work and it got me interested in biological anthropology. After graduating with my BA, I got the opportunity to work with Dr Berger and his team.

“At the moment, I am a full-time PhD student and work as a teaching assistant. The best thing about being a teaching assistant is that I get to communicate with students; I not only get to educate them about anthropology, but they also educate me. I get the opportunity to recognise their level of understanding of anthropology. We get to communicate about the importance of anthropology in this world.”

“Our generation gets to improve on the narrative.” – Ginika Ramsawak, archaeologist

“I used to borrow a lot of historical books from my local library as a child. The field continued to fascinate me as a teenager and my interest never faded.

“As an archaeologist, the best thing about my job is the people. Hearing stories about other faculties, I feel our field sincerely tries to improve on representation of marginalised voices. Archaeologists are some of the most open-minded people who are always willing to learn about other cultures. The spectacular views of the landscape are also a bonus.

“A young scientist in South Africa has to be aware of the social issues that constantly affect academia. This enables us to be researchers who are highly aware of what we reflect in our work, encouraging empathy. It is an exciting experience when you realise that our generation gets to improve on the narrative of the past through a fresh lens.”

“We are still navigating spaces that were designed to exclude us.” – Kimberleigh Tommy, biological anthropologist

“I first became interested in my field through watching documentaries on Egypt as a child; then, in my final year of my undergraduate degree, I was exposed to palaeontology through a lecturer who later became my supervisor in my honours year, Dr Job Kibii.

“To be a young scientist in South Africa in 2020 is challenging. We are still navigating spaces that were designed and constructed in such a way as to exclude us. Coming into these spaces now can sometimes be mentally draining. While navigating racial biases, we are also expected to perform and often outperform our white counterparts.

“Some of us are first-generation graduates and postgraduates; there is an immense pressure from our loved ones and communities and ourselves, ultimately, to perform and not disappoint anyone. It is also a time for hope – we are doing amazing research, we are seeing more and more young talented South African scientists take centre stage and do a brilliant job in their respective fields.”

“Being a young scientist in South Africa in 2020 is to actively change the ‘face’ of science.” – Keneiloe Molopyane, archaeologist (and Maropeng’s curator)

“Being a young scientist in 2020, a South African scientist, wow! I’ll be honest, if you had, a couple of years ago, called me a scientist I would have taken offence. The first image that comes to your mind when you mention ‘scientist’ is that of a man (typically white) in a lab coat and glasses. I, for one, did not view myself as such a person for obvious reasons.

“There is just so much pressure being a young researcher in South Africa in general, now add to that being a person of colour. The #BlackintheIvory movement (a global social media trend in which people of colour discussed the discrimination they’ve faced at institutions of higher learning) has brought to the surface a culture that needs to come to an end.

“Perhaps being a young scientist in South Africa in 2020 is to actively change the ‘face’ of science and be loud about it, bridging the gap and making science accessible to all that can benefit from it.”

“Imposter syndrome is a challenge for many of us young scientists!” – Kelita Shadrach, archaeologist

“I don’t have a nostalgic story about always wanting to be an archaeologist. I took the subject confusing it for palaeontology and in the very first lecture the Prof. said, ‘if you think this is about dinosaurs you can leave and change courses’. In shock I saw no one else leave so I stayed … for nine years (absolutely no regrets).

“[One of the challenges in the field] is keeping a confident position amongst other researchers. Imposter syndrome is a challenge for many of us young scientists! So if you are reading this then remember: Keep your chin up! You deserve to be where you are because you worked hard, not because you got lucky!”