Putting a face to a fossil: Meet John Gurche

Palaeoartist and anthropologist John Gurche knows his work has struck a chord with his audience when they react to his sculptures.

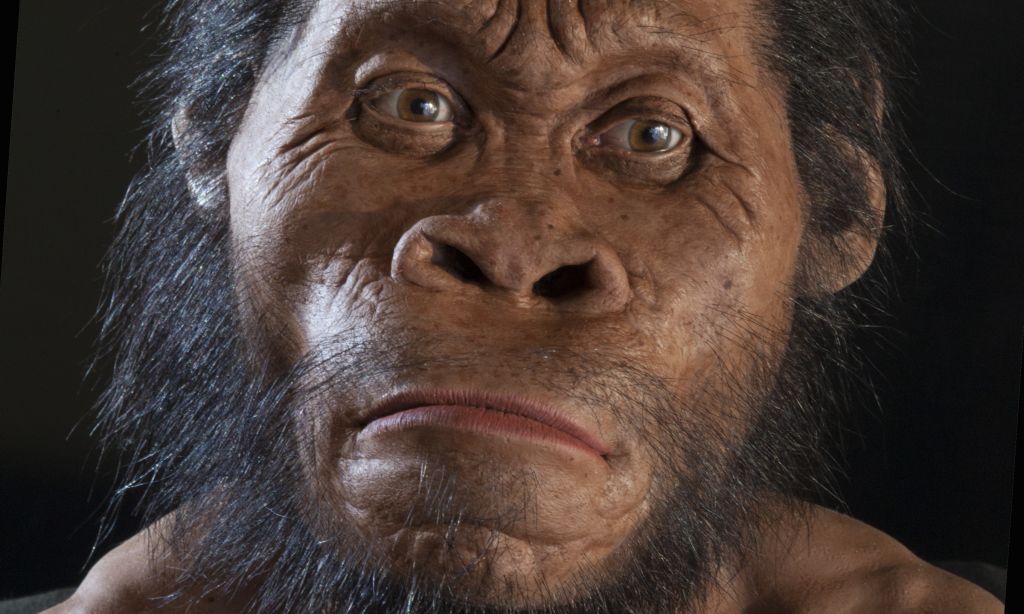

“The reactions that stick out for me are when people react to one of my sculptures as if it was alive. They react to it as if there’s a presence there, as if there’s something behind the eyes, and it isn’t just a sculpture,” he says.

“If I get that reaction – which I do often – it tells me that at least there’s something in the realism department that I’ve achieved.”

Visitors to Maropeng will get a taste of Gurche’s extraordinarily realistic creations in an upcoming exhibition titled Face to Face.

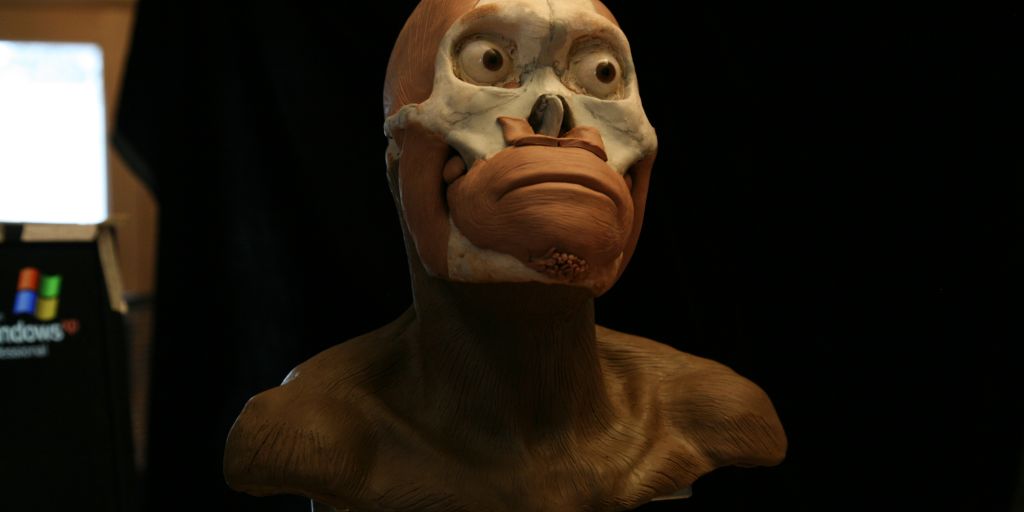

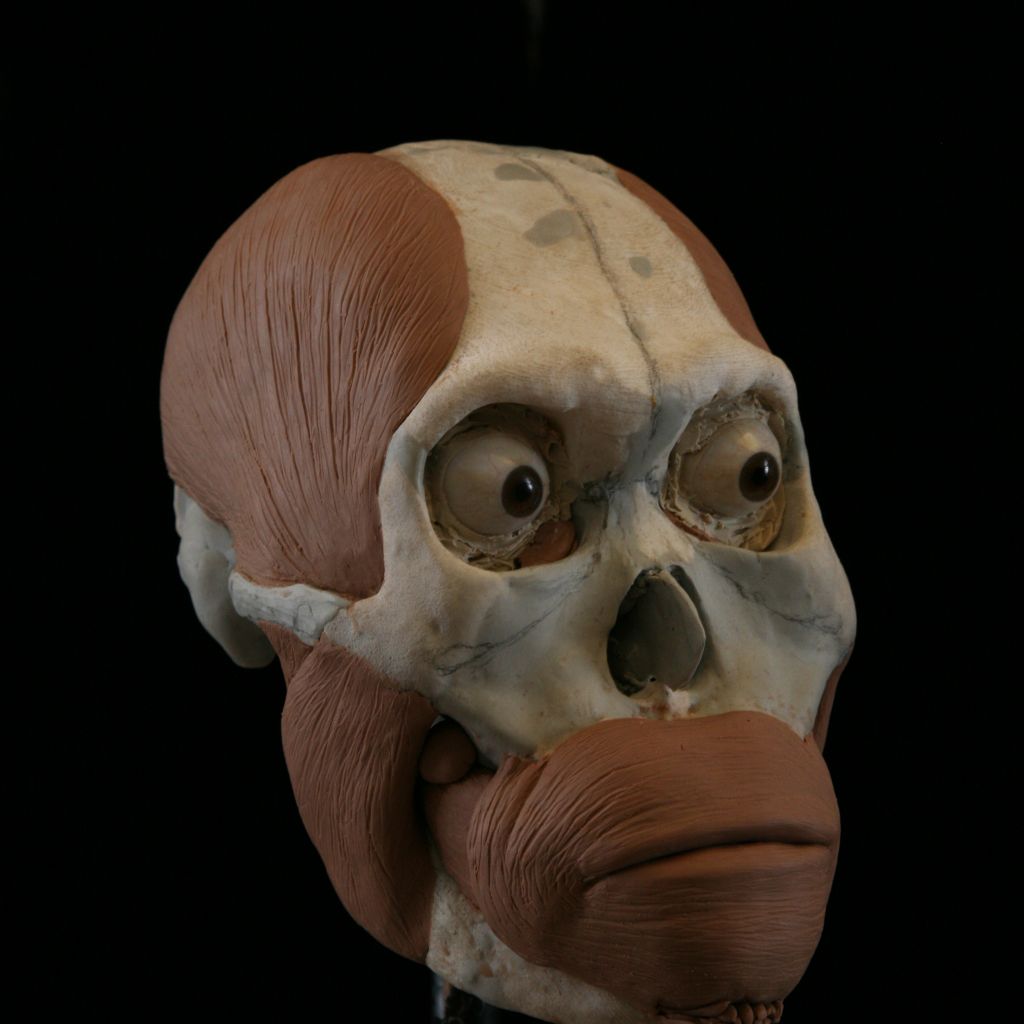

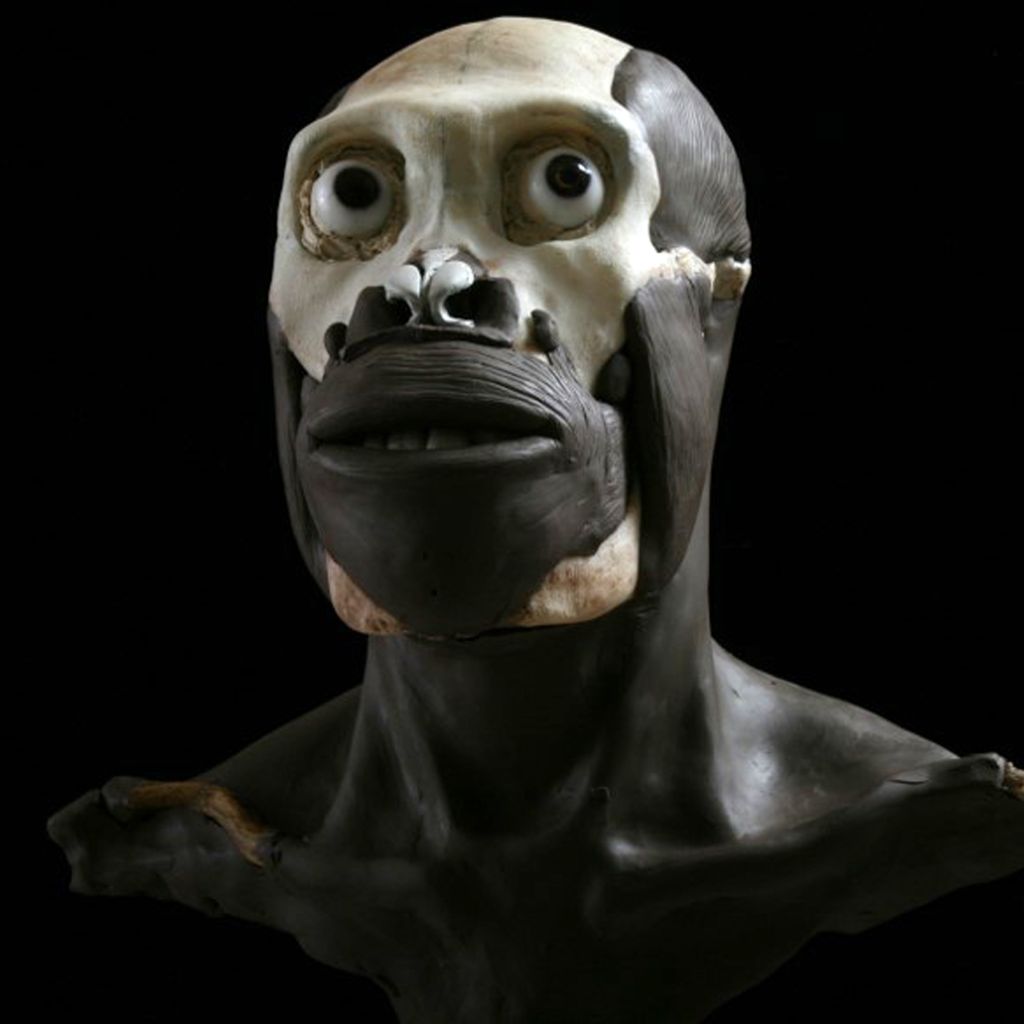

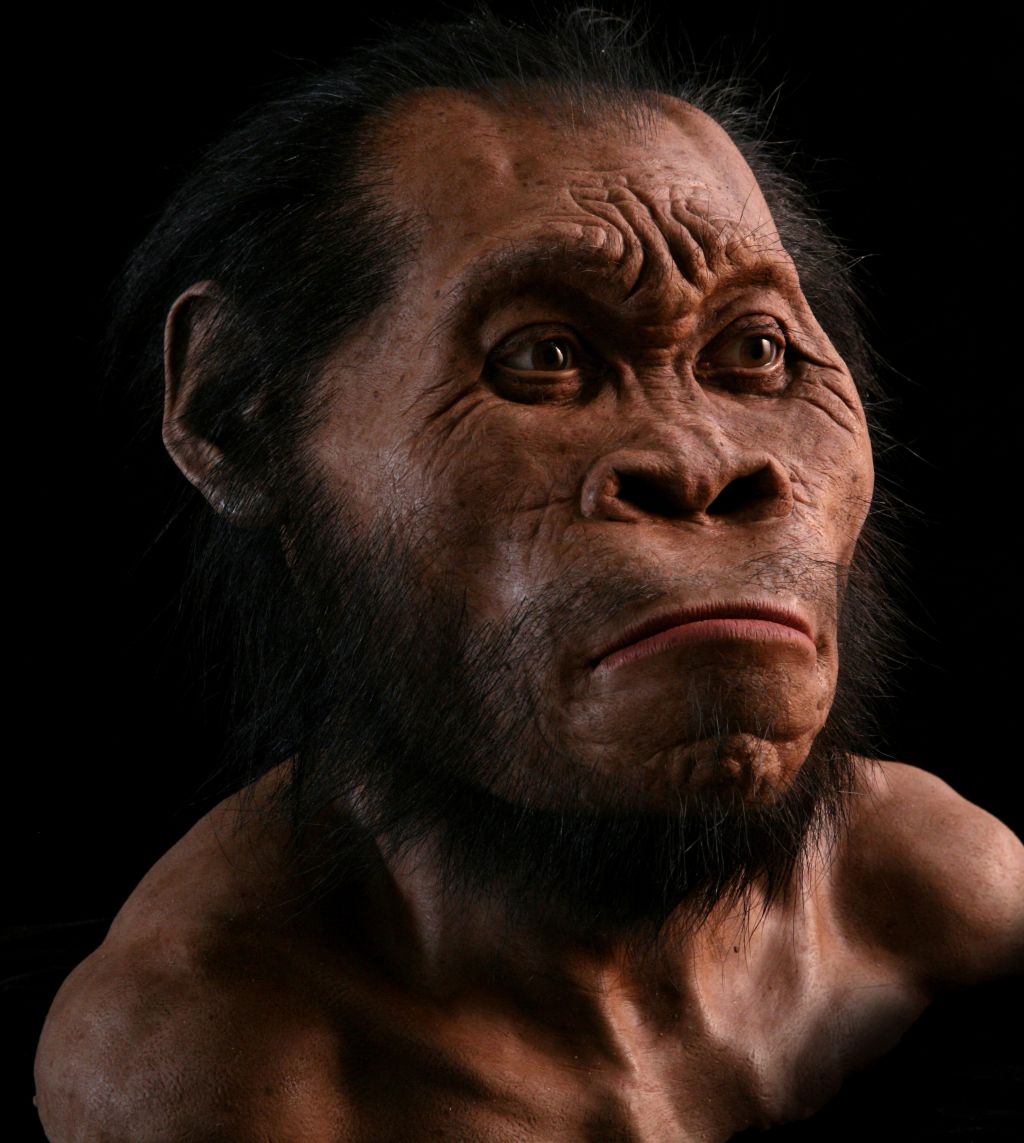

Face to Face will feature three sculptures by Gurche that have been specially commissioned by Maropeng: Homo naledi, Australopithecus sediba and Paranthropus robustus. All three species were discovered at excavation sites right here in the Cradle of Humankind.

You may be familiar with Gurche’s reconstruction of Homo naledi, commissioned for National Geographic magazine when the discovery was announced to the world in 2015.

Gurche’s creations bring to life mysterious creatures that are unearthed as fossils all over the world. His creations (and creations by artists like him) make the complex scientific investigation into our origins real and relatable for those of us who aren’t fossil hunters or palaeoscientists. Gurche says this sense of realism comes from the fact that these creations are firmly rooted in science.

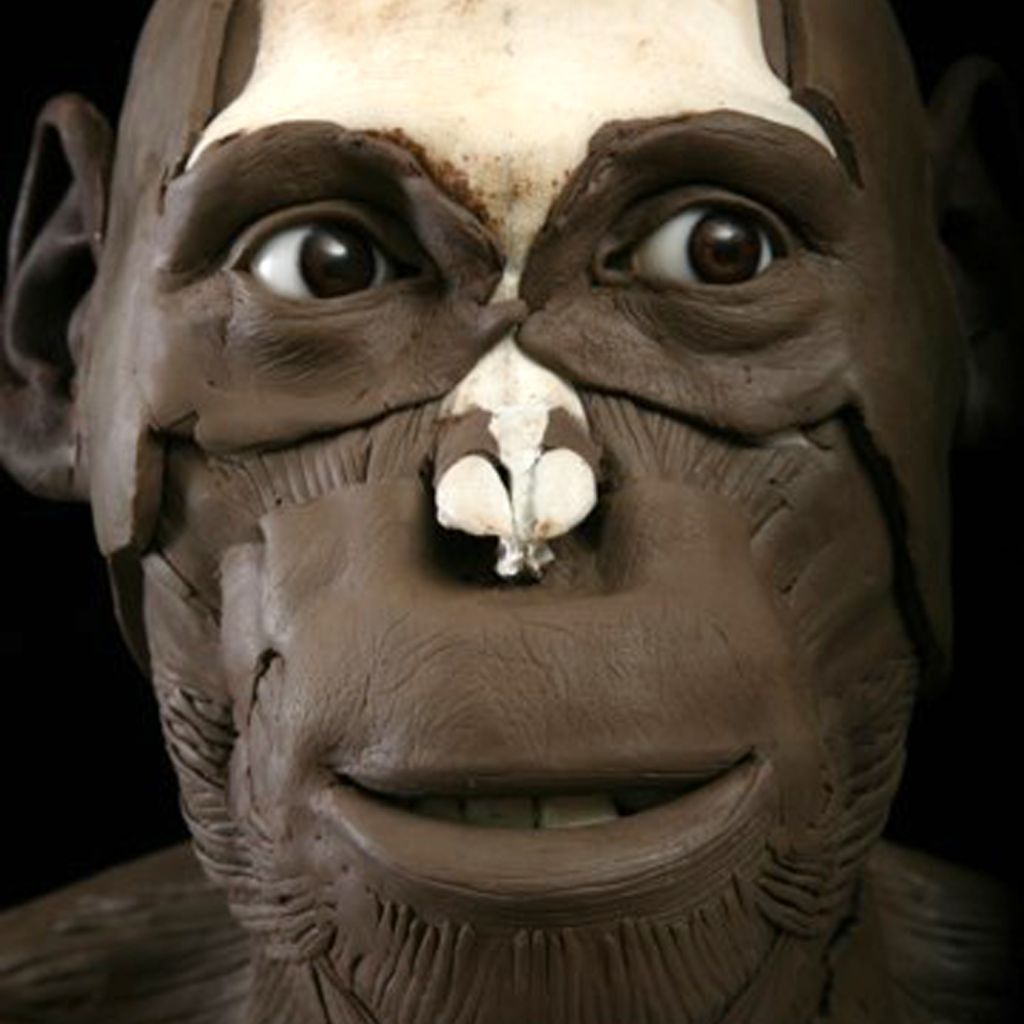

“Each reconstruction develops as a cumulative result of hundreds of anatomical decisions. I have a worksheet that’s 104 pages long, full of data and equations, that I use when I reconstruct a face.”

Facts and figures behind a face

This data and these equations often speak to the relationship between the bony anatomy and the soft tissue anatomy in a species. Understanding this relationship helps Gurche deduce what the face around a skull might look like.

“It turns out that there are quite a few relationships between bony anatomy and soft tissue anatomy that seem to apply to the whole branch of at least African apes and humans.

“And if you can find a relationship between, let’s say, the dimensions of the eye socket and eyeball diameter in humans, chimps, bonobos and gorillas, it’s going to give you a best guess for any extinct members of that [species].

“Now, can we do that with all the features of the face? No. There are many features where you don’t have such a luxury and so you have to dig a little deeper, and there are varying degrees of speculation, but usually it’s informed speculation.”

Gurche says brain size, for instance, is a good indicator of how thick the tissues in the face will be.

“Brain size has an effect on the amount of fat in the body and it’s reflected in the face in modern humans. The reason we have this subcutaneous layer of fat in our bodies and quite a lot of fat in our faces – unlike African apes – is because we have very large brains, outrageously large brains.

“We have had to accomplish a number of tricks to develop these brains, and some of them are anatomical or physiological. For example, the large amount of subcutaneous fat in the human body is thought to function as a nutritional buffer for a creature growing an outrageously large brain.

“Knowing that, you can begin to ask yourself questions about extinct hominins and you can relate fat content with brain size.”

Raising eyebrows

Things like eyebrows, though, are another story.

“We don’t have a very good idea of when something like eyebrows came into being. We use [eyebrows] a lot in visual communication. It’s a very mobile area.

“If you were designing a creature to make it very amenable to communication visually, you might say: Let’s put a marker in this very mobile place that has a lot of function in facial expressions. Let’s put a little fur strip above the eyes.”

This kind of thinking, Gurche admits, is purely in the realm of speculation. If you link eyebrows to communication, you might also look at the development of the Broca’s area in the human brain that controls speech.

“That little area begins to show up on casts of the inside of craniums about two million years ago. So it looks, to some people, like something’s happening there with the evolution of communication.

“Now, as you can see, I’m going pretty far out on a limb here, but at least it’s not pure speculation.”

A single silicone sculpture can take about four months to complete, with Gurche doing most of the work himself, bringing in a team only when it’s time to punch in the hair, which is an intensive process involving carefully attaching hundreds of hairs strand by strand to a sculpture.

It’s a lot of work, but Gurche says this kind of art helps us connect to our past in a unique way.

“I think it’s important to see these reconstructions as a way of connecting with the ancient hominins in question.

“I think presenting [viewers] with something that looks real and alive is important because it really brings home fully that these weren’t just abstractions. These aren’t just some bones that were in the ground. These were once living, breathing beings.”

Gurche has also reconstructed dinosaurs, and was even a consultant on the movie Jurassic Park, but human ancestors are his passion.

“When I’m working with dinosaurs, I have to just listen to the experts and base my work on that. It’s like taking an exotic vacation. But when I work on hominins it’s like coming home.

“It’s like this is us. It’s much more personal in a way – it’s the development of a fantastic creature in the history of the world, and it’s a much more personal thing.

“A long time ago, I developed a desire to be able to look these creatures in the eye. And so, this is about as close as I can come to that.”

A life-changing movie

Gurche’s own origin story goes back to a fascination with fossils when he was growing up in a southern suburb of Kansas City in the United States. The area, he says, was so rich in fossils that you could spot in streams and roadcuts.

It was an interest he nurtured through primary school, but then dropped in high school: “It was the late 1960s, so I was painting psychedelic posters and listening to my favourite rock’n’roll groups. I was in a band.

“And then I went to see the film 2001: A Space Odyssey and the whole history of life came crashing back in. And I realised that this film was about one of the most fantastic developments in the history of life on Earth – and that is the evolution of humans.

“I knew two things when I left the theatre: one was that I had to study human origins, and the other was that I wanted to work as an artist.”

Gurche has never looked back. His career path has seen him become an anthropologist and an artist, reconstructing extinct species for the world’s largest museum, education and research complex – the Smithsonian in the United States. He is currently an artist-in-residence at the Museum of the Earth in Ithaca, New York. In a Covid-impacted world, where many things have gone virtual, he hopes physical museums endure.

“I hope people don’t stop going to museums. I think there’s something to be said for standing next to a dinosaur skeleton instead of viewing it on screen. There’s something that screen experience really can’t replace, so I’m hoping that that will win the day.”

The parrot-like palaeoartist of the future

As Gurche painstakingly immerses himself in the reconstruction of creatures that existed millions of years ago, does he imagine that millions of years from now there will be another, vastly different kind of artist trying to reconstruct what humans were like?

“I’ve actually imagined that quite a bit. I don’t have high hopes for humanity surviving too much longer: we’re heading for the cliff at 90 miles an hour and we’re not putting the brakes on in any effective way.

“I think anthropologists have made the point that in many lineages, brain sizes have been increasing for a long time. One anthropologist I know thinks humans just got here, to this level, first. And he fully expects that if we were to go extinct, something would arise and take our place within that lineage.

“When I think of what that might be, I think of descendants of raccoons, I think of descendants of parrots or corvids [in the crow family]. The history of life is full of examples of a niche being vacated and other animals moving in to take over that niche. So I wouldn’t be too surprised if that happened.

“And I imagine that there is some sort of a digging implement, and it’s in the foot talon of a parrot or some descendant of a parrot. It’s digging down and it finds the remains of our civilization and it’s wondering about us, realising that someone got there before, to that niche, but blew it. And maybe it’s wondering about our mistakes.”

Here are some fast facts on the three species featured in the Face to Face exhibition:

Homo naledi is the most recent of these discoveries and evidence suggests this enigmatic species, discovered in the Dinaledi cave system in the Cradle, was present in the area as recently as 236 000 years ago, and in fact may have been around at the same time as our own species, Homo sapiens. Humans are the only surviving species in the Homo genus.

The evidence suggests this species may have deliberately disposed of its dead – a ritualistic behaviour that thus far has only been routinely observed in humans (there have been only anecdotal instances of other species doing this).

Paranthropus robustus was found at the Drimolen site in the Cradle, and fossils of this species date back from 1-million to 2.3-million years ago. Work being done at Drimolen is particularly exciting. Scientists say specimens discovered at the site, which span a few hundred thousand years, show evidence of microevolution – older specimens found at the site have smaller crania, suggesting less developed jaw muscles.

The theory is that this species developed larger crania and bigger jaw muscles as the climate in the Cradle evolved from a lush, green area to the more dry, arid landscape we’re familiar with today. This meant that the food available would have changed, and could have sparked this adaptation in the jaws of Paranthropus robustus.

The first Australopithecus sediba specimen was discovered in the Cradle of Humankind at what is now the Malapa site in 2008. Australopithecus, an early ancestor of modern humans, was much smaller than us and walked upright. Fossils of this particular species – Australopithecus sediba – are dated at 1.95-million to 1.78-million years ago (a time period that overlaps with Paranthropus robustus). This species has characteristics of both the australopithecines and the genus Homo, suggesting it was around at a time when the branch that would eventually lead to humans emerged.