“Little Foot”

”Tracking down “Little Foot”

The story of how “Little Foot” was found, more than 3-million years after he fell into the cave, is almost as remarkable as the skeleton itself.

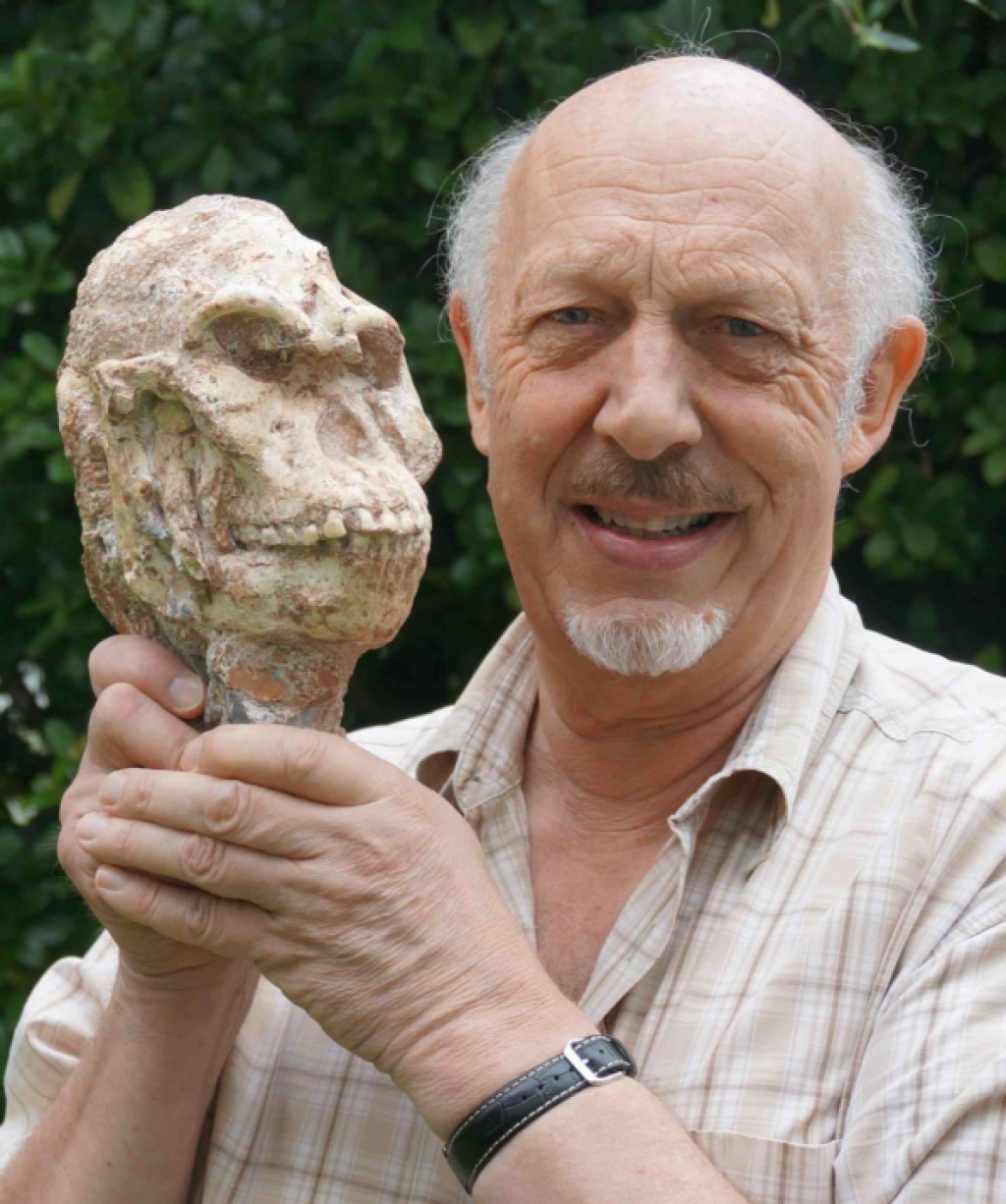

In 1994, palaeoanthropologist Professor Ron Clarke was in the workroom at Sterkfontein, sorting through a box of animal bones from the Silberberg Grotto in the caves, when he came across four foot bones which he realised belonged to an Australopithecus. The following year, he and Professor Phillip Tobias announced the discovery of the fossil StW 573, nicknamed “Little Foot”, consisting of four articulating foot bones. The bones had actually been cleaned out of breccia in 1980, but had not been recognised as hominid at that time. The discovery of the foot bones in itself was important, since comparatively few foot bone fossils of Australopithecus have been found.

Then, in 1997, Clarke discovered in the Wits Department of Anatomy more bones in a box of monkey fossils, which he realised also belonged to StW 573. One of the leg bones, a shin bone, appeared to have been recently broken. Clarke guessed that because there were bones from both left and right feet and legs, the rest of the skeleton could still be in the caves.

He approached his technical assistants, Stephen Motsumi and Nkwane Molefe, with a cast of the broken shin bone, and asked them to search for the piece from which it had been snapped in the vast and dark Silberberg Grotto – a task akin to finding the proverbial needle in a haystack. Searching with only hand-held lamps, the two men astonishingly found the matching bone after just two days. It was embedded in breccia, deep inside the Silberberg Grotto.

“Little Foot” is still lying partially in breccia, while Clarke painstakingly excavates it.

Once fully revealed, “Little Foot” will present unique insights into the world of our early ancestors.

How do we know “Little Foot” walked upright?

“Little Foot’s” anklebones are built to support the weight of a bipedal stride.

Even though “Little Foot” had a divergent big toe, which

enabled it to climb trees, researchers are certain that this early Australopithecus walked upright on the ground for much of the time.

Generally, palaeoanthropologists assess whether a hominid is bipedal by looking for signs of the following:

- a downwardly positioned foramen magnum (the spine entry point) on the skull;

- a spinal lumber curve that keeps the body upright;

- a shorter, broader pelvis for upright weight distribution;

- elongated legs that improve upright stride length;

- an inward-angled thigh bone (femur) to keep the legs more directly underneath the body;

- a big toe that is more in line with the other toes (instead of divergent), aiding walking.

Return to the Exhibition Guide.